Thyroid surgery

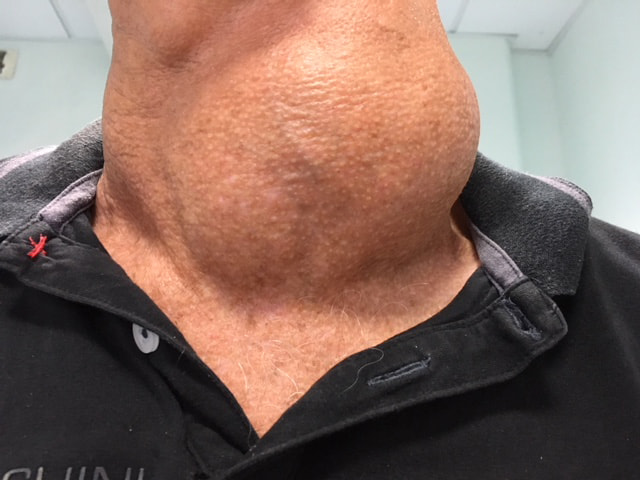

Thyroid pathologies are very common in the French population, from the benign nodule present in 5% of the population over the age of 50, to thyroid cancer, the 5th most common cancer in terms of incidence (number of new cases per year). When necessary, a thyroid surgeon can be called in to meet the operative demands of patients, endocrinologists and referring physicians. As a professional specializing in surgery of the face and neck, the ENT surgeon is an indicated referent in the care pathway of the patient suffering from surgical thyroid pathology.

Find out more about thyroid surgery from Dr. Delagranda, ENT and cervico-facial surgeon in La Roche sur Yon.

Thyroid, ultrasound and cytopuncture

The thyroid is an endocrine gland, an organ responsible for producing hormones in the bloodstream. Hormones are molecules that act as messengers and influence the functioning of other organs throughout the body. Thyroid hormones are essential to the basic functioning of the human body. In particular, they regulate the heart, muscles and digestive system, as well as body temperature, brain maturation and bone growth.

The thyroid is an organ located in the lower median part of the neck, measuring around 6 cm in height and 7 cm in width, and weighing around 25-30 grams. Schematically, it is described as butterfly-shaped, lying in front of the trachea (the central respiratory axis of the neck), consisting of two lobes positioned on either side of the trachea and connected by an isthmus, from which a small accessory lobe, known as the pyramidal lobe or Lalouette pyramid, may inconstantly arise at the top.

The structures in the vicinity of the thyroid account for the main risks of this surgery:

- Behind each thyroid lobe runs the recurrent nerve, responsible for innervation and movement of the vocal cords (1 nerve for each vocal cord), and thus for phonation and speech modulation.

- More or less adherent to the deep surface of the thyroid lobes are 4 or less other small endocrine glands called parathyroids, which play a key role in regulating calcium and phosphorus in the body, via the blood, bones, kidneys and digestive tract.

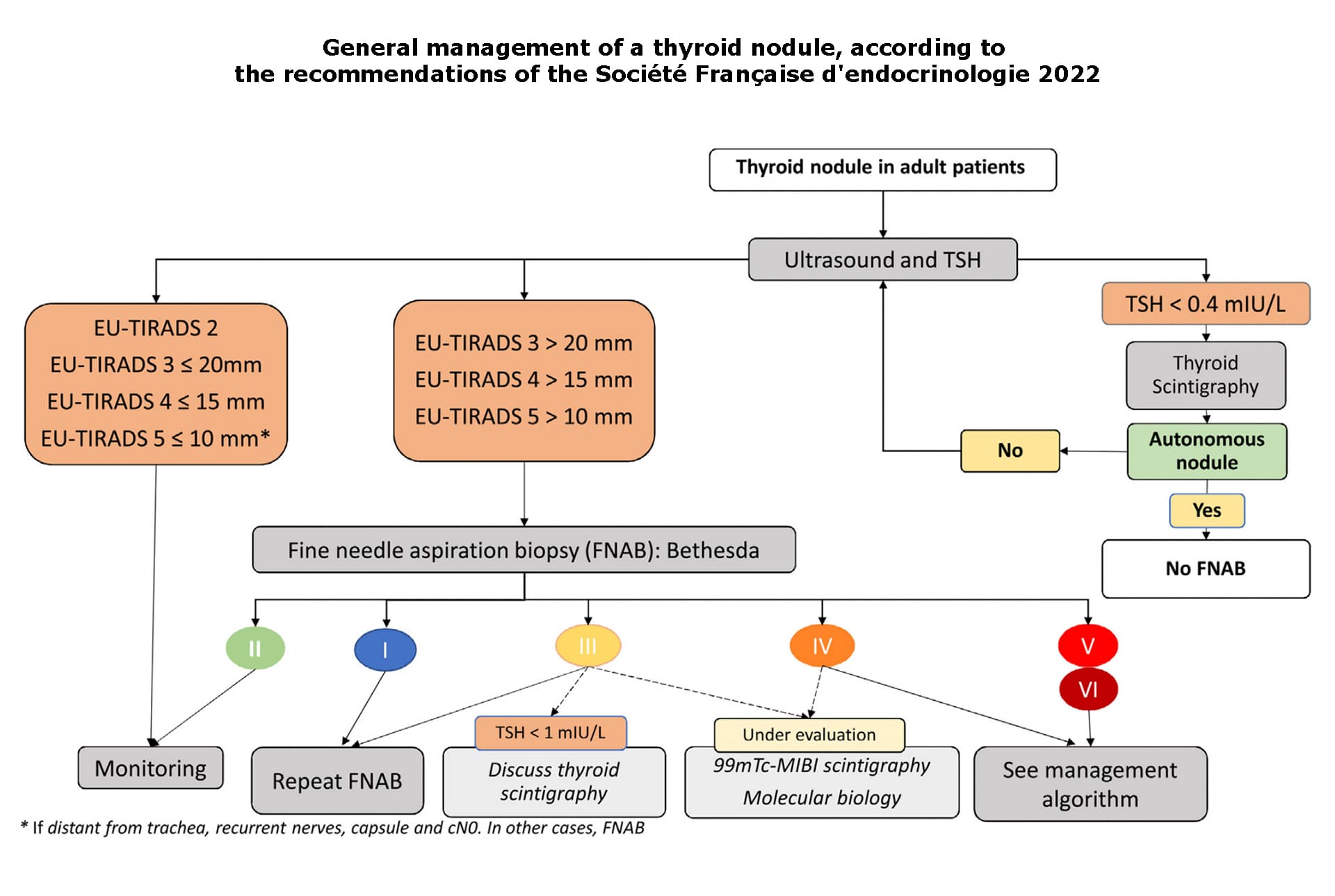

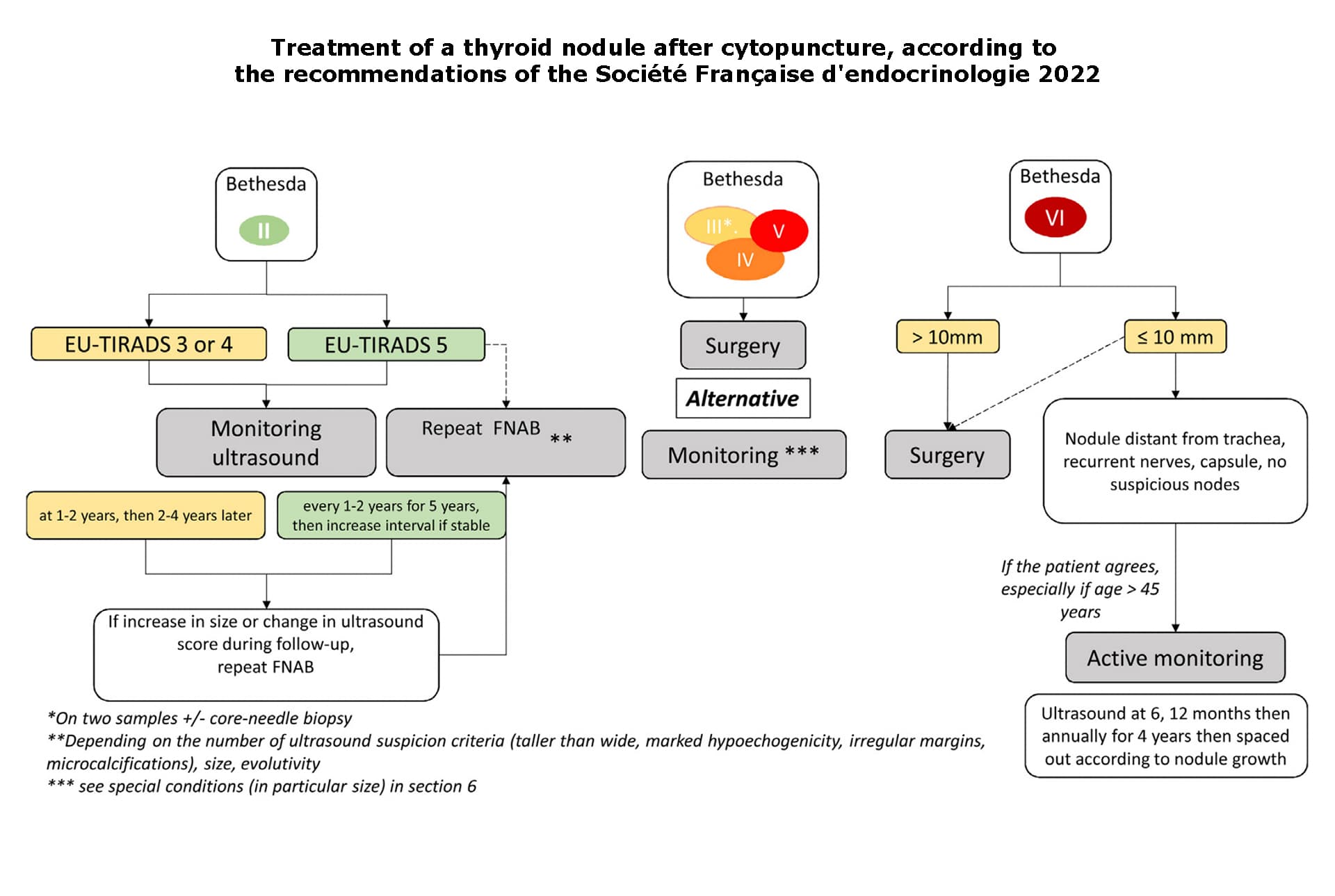

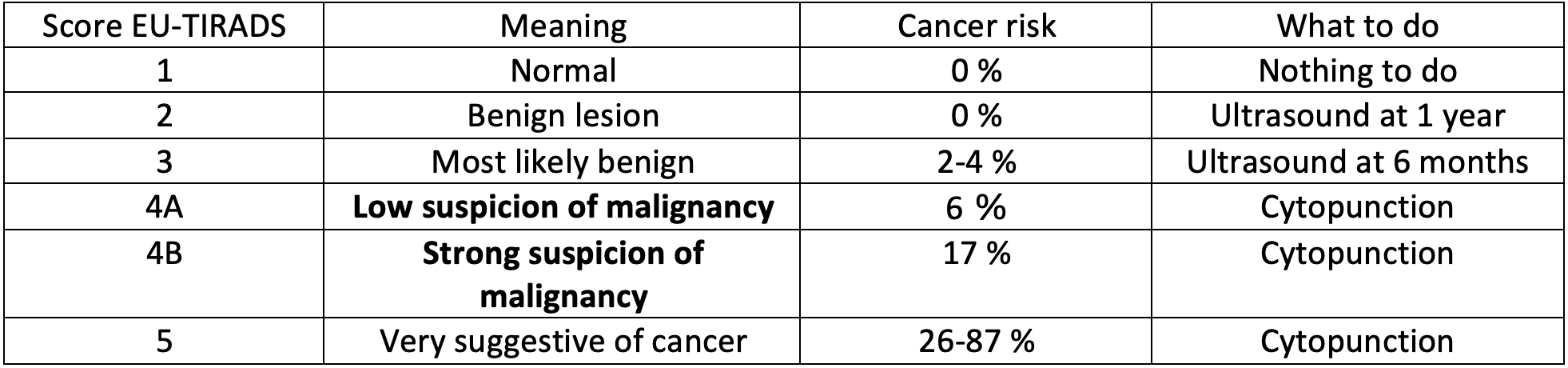

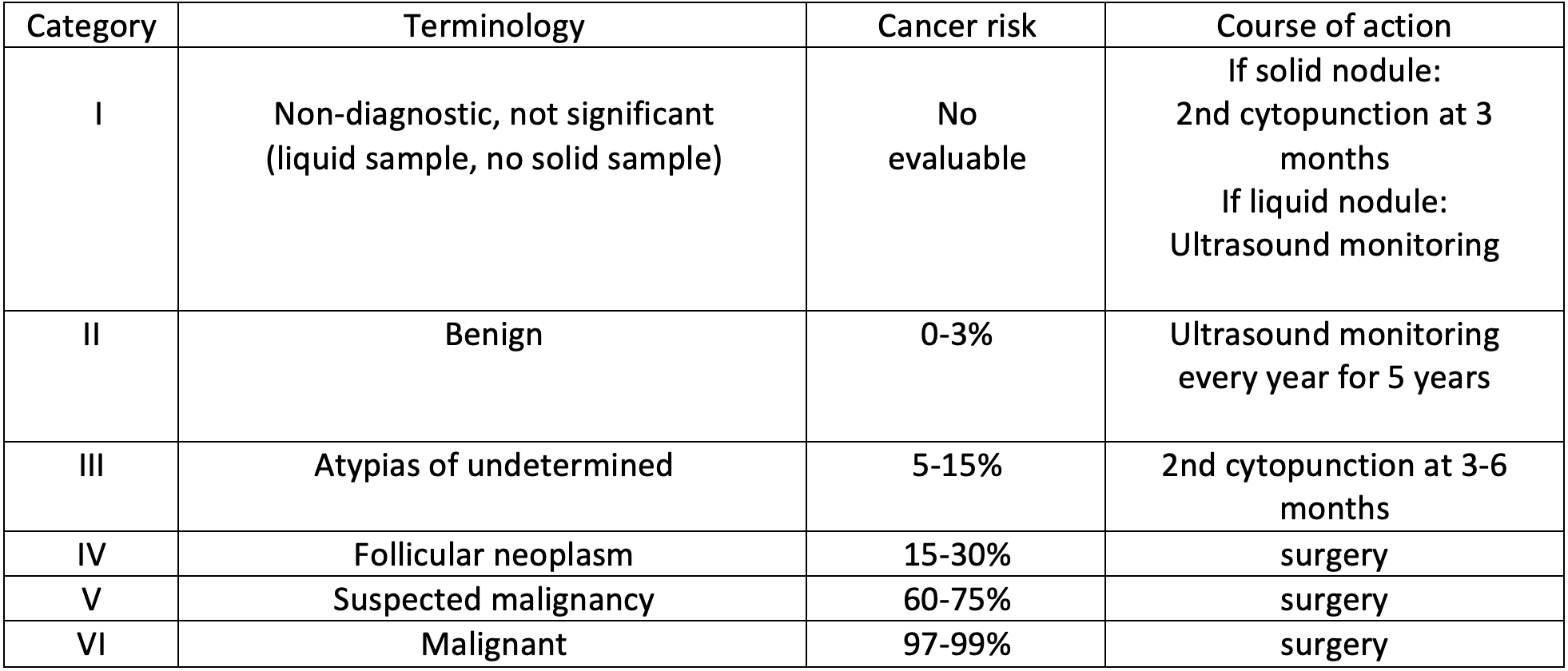

Thyroid nodules may be punctured depending on their size, the risk context of the family and on the indication of the sonographer, who has established a malignancy risk score called EU-TIRADS (European Thyroid Imaging and Reporting Data System). The result of the cytopunction further specifies the risk of malignancy, giving a percentage from which a therapeutic decision is derived. However, while the classifications are the same for all, specialist physicians may have slightly different approaches to the same result.

EU-TIRADS ULTRASOUND CLASSIFICATION

CYTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION BETHESDA

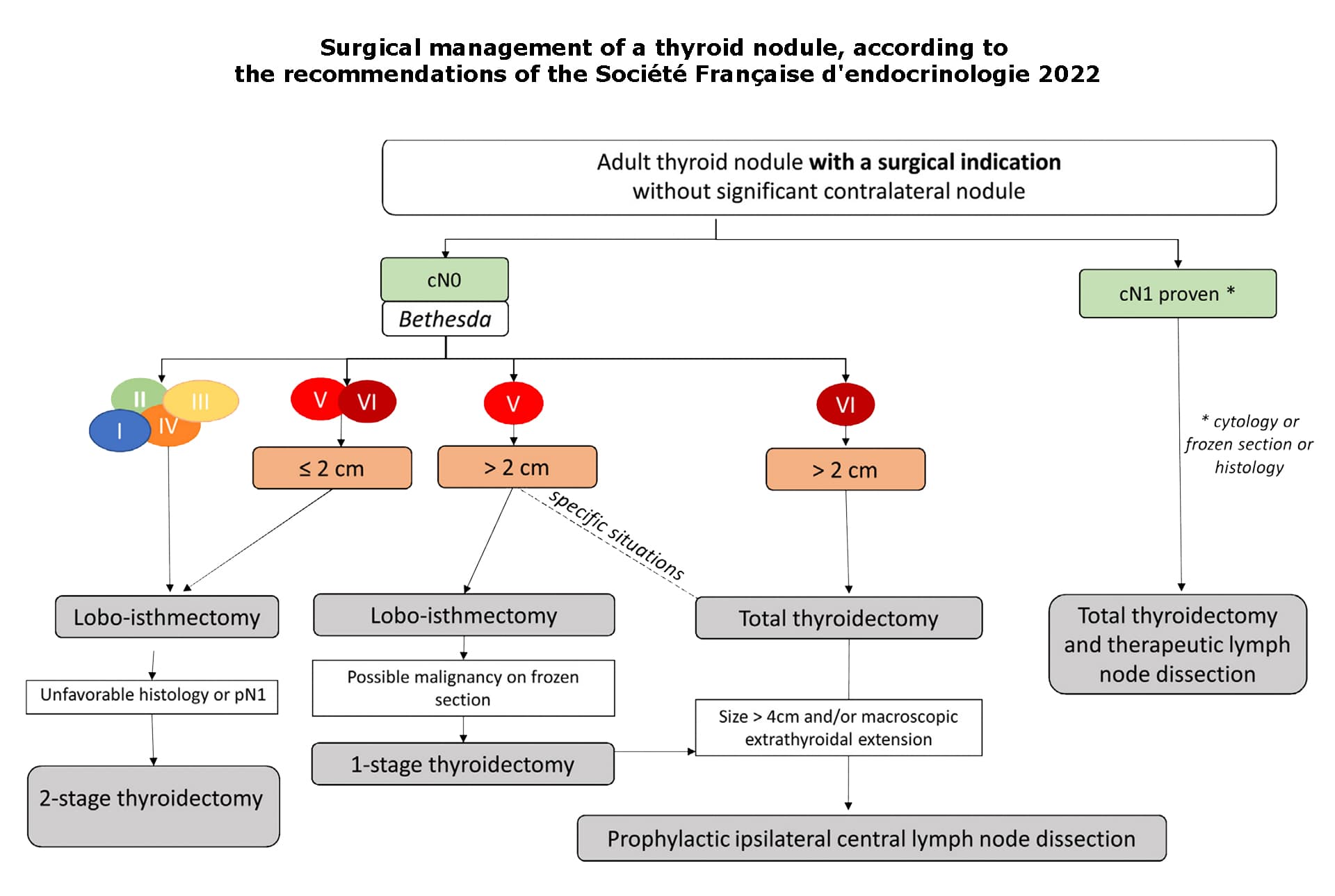

GUIDELINES BASED ON THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE FRENCH ENDOCRINOLOGY SOCIETY 2022

The main thyroid pathologies leading to consultation of a surgeon

In this section, we will not discuss thyroid pathologies responsible for a decrease in thyroid activity (hypothyroidism), but only those responsible for an increase in thyroid activity (hyperthyroidism), its size or the appearance of benign or malignant nodules.

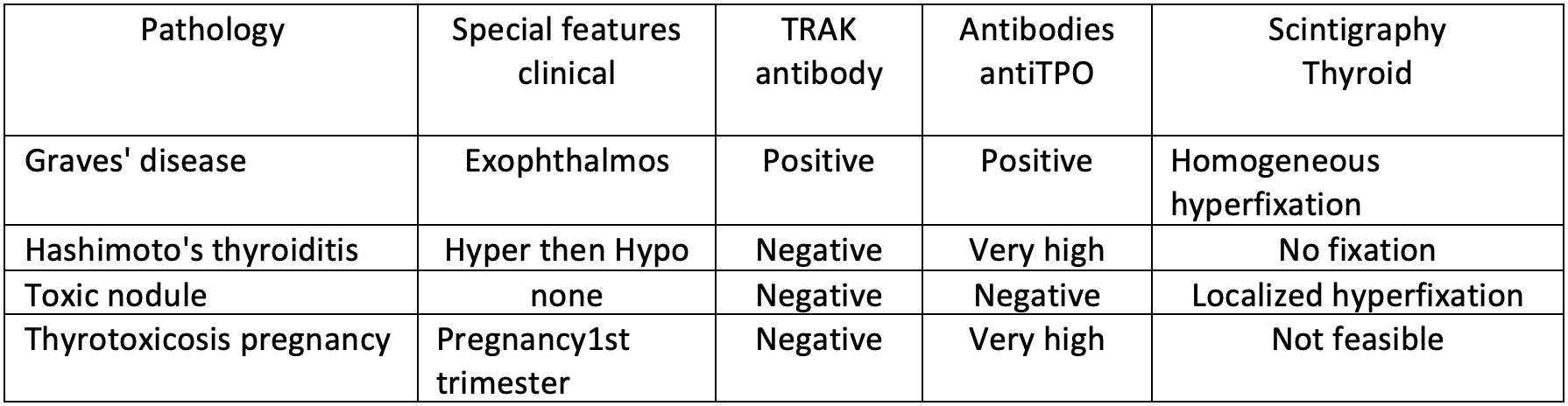

Grave’s disease

Grave’s disease is an autoimmune disease that affects women preferentially (ten women for every man) in the 20-40 age bracket, and is caused by the patient’s own production of antibodies that stimulate thyroid growth and hormone secretion. Anti-TSH receptor antibodies (TRAK) are the hallmark of the disease, but anti-peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) can also be found in 90% of cases, and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (anti-TG) in 25%. The result is symptoms of too much thyroid hormone in the body (elevated free T4, more rarely T3, and collapse of TSH levels) and/or the presence of an enlarged thyroid, responsible for a thickened, protruding appearance of the lower neck, known as a goiter. After a thorough examination and work-up by an endocrinologist, the first-line treatment is an antithyroid drug. Synthetic antithyroid treatments are administered for 18 to 36 months, with a remission rate of up to 50% only. The rate of recurrence increases with the duration of the disease, the volume of the goiter and the T3 level (>500ng/dl). Pregnancy should be avoided if possible with the most common synthetic antithyroid (carbimazol or Neomercazol©), as it can cause fetal malformations such as craniofacial (dysmorphia, choanal atresia, skin and hair aplasia), cardiac (interventricular communication) and esophageal atresia. Thyroid surgery is therefore often indicated in the long term.

Hyperthyroidism may correspond to Graves’ disease, but also to a toxic nodule, a thyrotropic adenoma, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (in the hyperthyroid phase), or transient thyrotoxicosis of pregnancy.

Signs of hyperthyroidism include a fast-beating heart (tachycardia), intense fatigue, weight loss despite increased appetite, accelerated bowel movements, a sensation of heat, excessive sweating, nervousness and tremors.

Benign nodules

The term “nodule” defines a generally oval-shaped tumour. Thyroid nodules are very common: an estimated 4% to 7% of the population have palpable thyroid nodules.

In 95% of cases, they are non-cancerous (benign). There are different types of nodule (cystic, colloidal, follicular, toxic), which need to be monitored regularly by ultrasound to ensure they are progressing well. The risk of developing a nodule increases with age, obesity, smoking, radiation exposure, iodine deficiency and the number of pregnancies.

Toxic adenoma and toxic multi-nodular goiter

Toxic (or autonomous) adenoma is a type of nodule resulting from the excessive proliferation of normal cells within healthy thyroid tissue. This adenoma is responsible for excessive secretion of thyroid hormones, and the resulting symptoms. When the thyroid is the site of several toxic adenomas, we speak of toxic multi-nodular goiter. If the adenoma is pre-toxic, T4 levels rise, but without the signs of hyperthyroidism, and the thyroid scans fix homogeneously. If the adenoma becomes toxic (4% of cases), T4 rises and signs of hyperthyroidism are present; it fixes on the scintigraphy and “extinguishes” the surrounding thyroid; this is known as an extinctive nodule.

Thyroid cancers

Thyroid cancers are very common (5th most common cancer in France), but generally have a good prognosis (90% survival rate at 10 years). The number of new cases of cancer ranges from 0.9 to 5.2 per 100,000 inhabitants per year, or 8,000 cases in France. Thyroid cancer accounts for 5% of nodules. Four times more common in women, they are frequently discovered by chance during the assessment of one or more thyroid nodules, or even during the analysis of a thyroid removed for another pathology (a goiter, for example). The risk of a nodule becoming cancerous is the same for a single nodule or a nodule in a multinodular goiter. Nodules are sometimes discovered during the assessment of cervical symptoms: pain, lymph nodes, cervical mass. Finally, certain types of thyroid cancer are genetic in origin, and form part of a family history of thyroid cancer.

Nodules that have appeared recently, before the age of 16 or after the age of 65, that are rapidly progressive, hard, irregular or fixed to palpation, with lymph nodes in the neck, with a change in voice (dysphonia) due to nerve paralysis, with a history of exposure to ionizing radiation before the age of 15, in the context of a family disease (medullary carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia) are at greater risk of being cancer.

The risk of cancer is independent of nodule size. Thyroid cancers are divided into four categories:

- Differentiated carcinomas: 90% of cases (including 90% papillary and 10% vesicular).

- Poorly differentiated or insular carcinomas: 3% of cases.

- Undifferentiated or anaplastic carcinomas: 2% of cases.

- Medullary cancers: 5% of cases.

Differentiated carcinomas

Differentiated carcinomas arise from follicular cells: in 3-5% of cases of papillary carcinoma, there is a genetic predisposition and several familial cases or association with other pathologies (kidney cancer, goiter, colon polyp). Lymph node metastases present in 50% of cases are close to the thyroid and more likely to be papillary, whereas distant metastases (mainly bone and lung) in 5-20% of cases are more likely to be vesicular.

Poorly differentiated or insular carcinomas

Poorly differentiated or insular carcinomas originate from follicular cells: they affect older people, are larger and give rise to more lymph node metastases (50 to 85% of cases) and distant bone and lung metastases (30 to 85% of cases).

Undifferentiated or anaplastic carcinomas

Undifferentiated or anaplastic carcinomas originate from follicular cells: they affect people over 60-80 years of age, increase in size very rapidly, and metastasize in over 50% of cases. They have the poorest prognosis.

Medullary cancers

Medullary cancers originate from calcitonin-producing C cells: in 70% of cases, they are isolated to the patient, and in 30% of cases, they run in families, constituting a hereditary form that is passed on to descendants in one out of two cases, and integrating with other pathologies (pheochromocytoma, hyperparathyroidism, megacolon, etc.) to form a multiple endocrine neoplasia (NEM).

Who is concerned by thyroid surgery?

Surgery is indicated in cases of:

- proven thyroid cancer by cytopuncture under ultrasound.

- single or multiple toxic adenomas (toxic multi-nodular goiter).

- benign nodule causing functional or cosmetic discomfort.

- benign nodule whose size is increasing significantly and/or rapidly (the size limit for deciding to remove a nodule is subject to discussion between specialists).

- nodules whose benign or malignant nature cannot be formally established.

- Graves’ disease, in case of resistance or contraindication to antithyroid treatment.

Purpose of surgery

The aim of surgery is to remove the pathological thyroid, either in its entirety (total thyroidectomy), or the diseased half (hemi-thyroidectomy or lobectomy).

Isolated removal of a nodule, known as “enucleation”, is no longer indicated according to best practice.

Surgery is usually performed under general anaesthetic, in the operating theatre, and usually requires 2 to 3 nights’ hospitalization. The duration of the operation usually varies from 1 to 2 hours, depending on the procedure performed (partial or total removal of the gland, associated lymph node dissection). Modern intraoperative nerve monitoring tools, known as NIM (nerve integrity monitoring) and APS (automatic periodic stimulation), can help the surgeon to precisely control the location of the recurrent nerves for NIM, and limit significant stretching of the nerve for APS.

The patient is intubated with a specific probe for NIM, and the surgeon makes a horizontal incision in the lower, central part of the neck, ideally in a natural fold of the skin to conceal the scar. The incision depends on the type of procedure and the size of the lesion to be removed. It generally measures between 4 and 6 cm. It’s important to know that the lesion removed by the surgeon is most often analyzed during the operation. Depending on the results of this “extemporaneous” analysis, the surgical procedure may be modified, and the operation lengthened or shortened. At the end of the operation, 1 or 2 Redon drains are placed, tubes whose role is to aspirate secretions that accumulate in the operated area in the usual way. They will be removed after a few days, before your discharge from hospital, depending on their abundance and at the discretion of your surgeon.

Complications associated with thyroid surgery

As with any surgical procedure, there may be some discomfort, notably a feeling of tension in the operated area, but the post-operative period is generally painless.

- Post-operative bleeding and hematoma: As the thyroid gland is richly vascularized, this risk must be booked. In the event of abundant bleeding or a voluminous hematoma potentially compressing the trachea, a new operation may be necessary.

Neck and swallowing pain: during surgery, the operating position requires the neck to be in hyper-extension. In addition, the surgeon approaches the thyroid after having cut the skin, pulling apart the muscles in front of it, which are involved in laryngeal movements (breathing, swallowing, phonation). These procedures explain the pain that may be felt during the first few days, but which is alleviated by painkillers. - Voice disorders: often minor and temporary, they are due to dissection of the recurrent or lower laryngeal nerves (nerves that innervate the vocal cords and are responsible for their movement), which are very sensitive to simple stretching. Modern intraoperative nerve monitoring tools called NIM or APS are used to limit the risk. Even with proper monitoring, voice disorders are not uncommon, and may sometimes require speech therapy. Finally, in the case of surgery for cancerous pathology, it is sometimes necessary to sacrifice a recurrent nerve in order to control the disease.

- Blood calcium disorders: rare in partial thyroidectomy, more frequent in total thyroidectomy, these are due to dysfunction of the parathyroid glands located deep inside the thyroid gland. Generally transient, they usually manifest as tingling in the fingers, feet or around the mouth, cramps or transit disorders (constipation). In some cases, they simply require blood monitoring and calcium supplementation by mouth for several days. More rarely, these disturbances may lead to an extended hospital stay for intravenous supplementation in the case of very serious disturbances. In exceptional cases, lifelong supplementation may be necessary if the parathyroid glands are permanently damaged.

- Infection: infection is inherent to any surgical procedure, and is evidenced by an opening in the scar and/or pain and/or a dirty, purulent discharge. It may be encouraged by poor suture tolerance or poor local care. Antibiotic prescription is often necessary, and scarring results may be altered.

- Healing abnormalities: The healing process lasts several months, with scars evolving up to 1 or 2 years after surgery. Skin scars may become or remain inflammatory for several months, possibly warranting local corticosteroid injections. Very large, progressive hypertrophic scars (keloids) are occasional and may warrant further treatment.

- Hypothyroidism is not a complication, but an expected and unavoidable consequence of total thyroid ablation. As thyroid hormones are necessary for the body to function properly, it is essential to ensure lifelong hormone replacement therapy, with regular blood test monitoring in conjunction with the endocrinologist and attending physician. In the event of partial removal of the thyroid gland, it may be necessary to provide temporary hormone replacement therapy.

Frequently asked questions

Here is a selection of questions frequently asked by Dr Delagranda’s patients during consultations for thyroid surgery in La Roche-sur-Yon.

I take anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents (such as Aspegic, Kardégic, Plavix, Clopidrogel, Previscan, etc.). Do I need to stop them for the operation?

Except in special cases, you should stop taking your medication a few days before and after the operation to limit the risk of bleeding and hematoma. Your surgeon or anaesthetist will inform you of the time limits to be respected, depending on your treatment.

How long do I need to protect my scar?

Once the sutures have been removed and your surgeon has checked that the scar has healed properly, you will need systematic sun protection using sunscreen for a period of 1 year. Healing creams can also be recommended by your surgeon or pharmacy, to be applied daily for the first few months. The aim of these treatments is to ensure the best possible aesthetic appearance of your scar, which can be modified up to 1 or even 2 years after surgery.

I have a benign thyroid nodule and I don't want to have surgery. Are there any other solutions?

In the case of a confirmed benign nodule, and depending on certain criteria, it is sometimes possible to propose a partial procedure, using radiofrequency or alcoholization. The aim is to reduce the volume of the nodule, without removing it, during an outpatient procedure under local anaesthetic, without cervical scarring. Don’t hesitate to ask your surgeon for further information during your consultation.

I've had thyroid cancer surgery. Will I need further treatment?

In the case of thyroid cancer, additional surgery may be required, particularly if partial surgery is initially performed. In addition, post-surgical treatment with radioactive iodine may be decided at a multidisciplinary consultation meeting attended by several thyroid cancer specialists. If this treatment is indicated, the details will be explained to you.

I've been told I need another operation. Is this normal?

In the case of thyroid cancer, additional surgery may be necessary. Extemporaneous analysis of the surgical specimen during the operation provides a rapid reading that guides the surgeon’s action. In some cases, the final, more in-depth analysis may differ from the initial results of the extemporaneous analysis, and a complementary procedure may be required, leading to a new operation. Similarly, a small fragment of thyroid may have been left behind after a total thyroidectomy, for reasons of safety for the recurrent nerve, and years later be responsible for a recurrence of the disease that prompted the initial operation.

Fees and procedure coverage

Thyroid surgery is covered by health insurance. Contact your mutual insurance company to find out how much coverage there is for any extra fees.

Do you have a question? Need more information?

Dr Antoine Delagranda is available to answer any questions you may have about thyroid surgery. Dr Delagranda is a specialist in ENT and Cervico-facial surgery at the clinique st-Charles, la roche sur yon, france.

ENT consultation for thyroid surgery in Vendée

Dr Antoine Delagranda will be happy to answer any questions you may have about thyroid surgery. Dr Delagranda is a specialist in ENT surgery at the Clinique Saint Charles in La Roche-sur-Yon in the Vendée.